For a Truly Representative House, which is better: Single-Member or Multi-Member Congressional Districts?

The answer is not obvious: While large multi-member districts promise greater ideological diversity, the advantages of small single-member districts are quite significant.

The question of whether members of the House of Representatives should continue to be elected from single-member districts, or instead from multi-member districts, is an ongoing and sometimes heated debate with both sides presenting compelling arguments.

Single-member district (SMD) refers to an electoral district represented by a single legislative representative. Members of the House of Representatives have been elected exclusively from single-member districts since the 92nd Congress (1971-1973), when legislation mandating their use came into effect. Prior to that, some members were elected from multimember districts (MMDs) which are geographically defined districts electing more than one Representative; or in general ticket elections, whereby a state elected all of its representatives at large without geographically defined districts.1Congress.Gov: Election Policy Fundamentals When conducting elections in MMDs, various “proportional voting” methods can be utilized to elect several Representatives from a much larger pool of candidates.2Wikipedia: Proportional representation Perhaps the most common method used is Party-List Proportional Representation, in which political parties present lists of candidates, and voters choose a party list rather than individual candidates.

This debate centers on how best to achieve fair and effective representation in the House: While MMDs promise greater diversity, SMDs provide several significant advantages that are not available from MMDs. The most compelling argument for MMDs is that it would enhance ideological diversity in the House by ensuring smaller parties gain seats and reduce wasted votes. However, as explained in this article, to the extent that diversity is improved, that benefit is more than offset by forgoing the benefits of SMDs. With a substantially larger House, as required by the Constitution’s one-person-one-vote equality requirement,3This would require over 6,000 Representatives, resulting in an average congressional district population of approximately 50,000. those benefits would include lower campaign costs, stronger local accountability, minimal gerrymandering, and reduced party influence.

Because SMDs create a system where a wider range of citizens can run for office, and where Representatives are more directly connected to their communities, we believe it is the better solution to fulfill the House’s fundamental purpose of serving the American people. However, before substantiating that conclusion, we should explore to what extent MMDs actually provide better diversity than SMDs. One challenge to answering this question is that some analyses don’t provide a true apples-to-apples comparison with respect to the equalizing the average constituency size. For example, in advocating for MMDs, a New York Times editorial titled A Congress for Every American used a strikingly unbalanced analysis: For their Massachusetts example, they compared 13 Representatives seeking office in three multimember districts to nine single-member district elections – why not use 13 single-member districts for that hypothetical comparison? And in their Texas example, they compared 51 Representatives seeking office in 11 multimember districts to 36 single-member district elections – why not use 51 single-member districts as a basis for that comparison? They also disregarded the conspicuous benefits of SMDs that would be forgone. It seems to be fairly common for such advocacy pieces to be similarly biased.

It should be pointed out that this debate is tangential to Thirty-Thousand.org’s mission of advocating for a substantially larger House of Representative: Whether one favors SMDs or MMDs, a substantially larger House would produce significant benefits for a variety of reasons as explained by our website. However, many of those benefits are predicated upon the assumption that congressional elections will continue to be conducted from smaller SMDs. As explained herein, those benefits would diminish significantly if Representatives were elected from MMDs.

We believe those arguments are self evident upon deeper reflection on this subject; however, realizing that this debate is fraught with strong sentiments, we sought to produce an objective comparative analysis of SMDs versus MMDs. Towards that goal the artificial Intelligence (AI) systems, Gemini Pro and Grok were enlisted to apply their considerable deep research and analytical capabilities to this question by reviewing the relevant information provided by Thirty-Thousand.org, along with any other information they could access, in order to provide an entirely objective analysis.

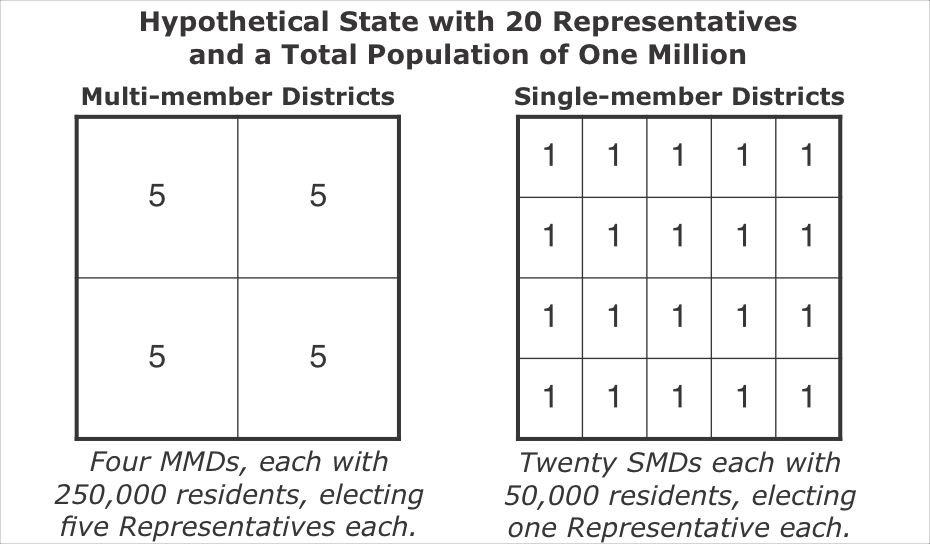

As the basis for their comparative analyses, Grok and Gemini were asked to assume that under either scenario, SMD or MMD, the average constituency size per Representative would be identical. Specifically, the hypothetical was for a state with a total population of one million. In the MMD scenario, this state is divided into four congressional districts of 250,000 residents each, each with five Representatives. In the SMD scenario, it is divided into 20 single-member districts, each with 50,000 residents. That is, in either scenario, there are 50,000 residents per Representative. That hypothetical is illustrated below.

For the scenario described above, what is the additional representational diversity that could be expected from utilizing MMDs rather than SMDs? We posed this question to Grok and Gemini Pro, and both agreed that the MMDs would result in significantly more diversity.4Grok and Gemini analyses as of September of 2025. Though they were not able to offer precise estimates, the highest estimate is that it would be 20 to 40% more diverse.5As explained by AI: “This diversity gain, derived from AI analyses of electoral models, is quantified using ideological spectrum models—such as DW-NOMINATE scores that map politicians’ voting records on a left-right axis—and party entropy scores, which measure the informational diversity (or ‘spread’) of party representation in a legislature; higher entropy indicates a broader range of viewpoints, often 20-40% greater in MMDs due to their ability to elect multiple winners per district.” See endnote for additional information about this estimate.

However, even taking that into account, both Grok and Gemini concluded that small SMDs better serve the House’s purpose of representing and serving the citizenry. The reader is encouraged to read Grok’s report and Gemini’s analysis for a deeper understanding of their arguments. Provided below is an elaboration of why they both reached the same conclusion.

The Big Picture

At the heart of the MMD argument is the principle of proportionality. In a multi-member system, seats are allocated based on the percentage of votes each party or candidate list receives. This mathematical precision often leads to a legislature that better reflects the popular vote, making it more likely that minority parties and diverse ideological viewpoints secure a voice that might otherwise be marginalized in a winner-take-all SMD system. The theoretical benefit is undeniable: Every vote “counts”, and the composition of the legislative body reflects the electorate’s preferences with greater fidelity. This can be particularly appealing in highly diverse areas, where various groups might feel unrepresented under a purely winner-take-all model. Of course, because of their greater complexity, the proportional voting methods can be more confusing for the voters than SMD elections, which could undermine the public’s acceptance of the election results.

Though both Grok and Gemini agree that MMDs are expected to produce superior vote-to-seat proportionality and ideological diversity, a closer examination reveals that small SMDs offer a more robust and effective system for ensuring genuine representation and service to the citizenry. Their analyses, informed by electoral theory and practical considerations, argue that the nuanced advantages of small SMDs — from reduced campaign costs to enhanced local accountability — ultimately make that the better choice for fostering a responsive and accessible democracy.

They agree with Thirty-Thousand.org that the pursuit of proportionality in MMDs frequently comes at a significant cost to other vital aspects of democratic representation. One of the most immediate and impactful consequences is the escalation of campaign costs. The larger multi-member districts, by their very nature, require more resources to effectively reach a wider and more varied electorate, especially when the number of competing candidates are far more numerous than in SMDs. Those candidates must invest in more extensive advertising, larger campaign staffs, and broader outreach efforts. This financial burden disproportionately favors wealthy individuals, well-funded political parties, and candidates with access to powerful donor networks. The result is a system that inadvertently erects barriers to entry for ordinary citizens, independent candidates, and grassroots movements, effectively limiting the diversity of individuals who could otherwise realistically aspire to public office. This financial gatekeeping becomes a practical reality in most implementations, undermining the very notion of broad representation it claims to uphold.

Furthermore, the local connection between a Representative and their constituents often becomes attenuated in MMDs. When several Representatives serve a single large district, the direct, personal bond that is crucial for effective representation is diluted. Citizens may find it less clear who to approach with specific local concerns, and Representatives, in turn, may struggle to identify and champion the unique needs of distinct communities within their sprawling district. This diffused accountability can lead to a less responsive government, where the specific grievances of a neighborhood or a particular demographic community might get lost in the broader mandate of a multi-member delegation. The ability of a constituent to directly and unequivocally hold their Representative accountable is a cornerstone of democratic health, and this direct line is effectively eliminated in MMD systems.

Another significant concern with MMDs is the potential for increased party control and the diminishment of individual candidate agency. Many proportional MMD systems rely on party lists, where voters cast their ballots for a party rather than individual candidates, and the party then determines which candidates fill the allocated seats. This mechanism vests immense power in party leadership, who control the selection and ranking of candidates on the list. While this can streamline the legislative process by ensuring party cohesion, it can also lead to Representatives who are more beholden to party dictates than to the specific needs or preferences of their constituents. The incentive structure shifts from direct constituent service to maintaining favor with party leadership, potentially alienating voters who seek independent-minded Representatives. It is also worth noting that in Europe, where proportional representation has long been the dominant electoral system for national parliamentary elections, party membership and voter participation have been on a consistent decline in recent years. Regardless of the extent to which there may be a causal relationship, the fact is that too many voters likely feel unrepresented by a party-centric electoral system.

In contrast, small SMDs directly address these shortcomings, cultivating a form of representation that is both deeply localized and inherently more accessible. The defining characteristic of small SMDs is their more manageable size, which triggers a cascade of benefits for democratic health, as follows:

Firstly, significantly reduced campaign costs are perhaps the most compelling advantage. In a smaller district, candidates can effectively campaign through direct engagement, local media, and grassroots organizing, dramatically lowering the financial bar for entry. Moreover, smaller congressional districts substantially diminish the incumbent’s advantages relative to being reelected, making it much more affordable for challengers to be elected. And finally, the impact of “dark money” would be greatly reduced with smaller SMDs as opposed to fewer large MMDs.6In a House with over 6,000 Representatives elected from small, 50,000-person districts, dark money’s influence is drastically reduced, as its resources are spread too thin to dominate hyper-local, low-cost campaigns driven by personal engagement—far more so than in larger multi-member districts, where higher costs and party reliance give external funding more traction. This democratizes the electoral process, making it feasible for a broader spectrum of individuals—teachers, small business owners, community organizers, and those without wealth or political connections—to run for office. This leads to a more diverse pool of candidates, not just ideologically, but also socio-economically, ensuring that the legislative body better reflects the diverse backgrounds of the citizenry it serves.

Secondly, small SMDs foster an unparalleled level of local accountability and a strong Representative-constituent bond. With a single Representative serving a clearly defined and usually a more homogeneous geographic area, constituents know precisely who their advocate is in government. This direct link facilitates easier communication, allows for focused attention on local issues, and makes it simpler for voters to hold their Representative directly accountable for their actions and performance. This direct line of communication and responsibility strengthens the trust between the citizenry and their government, as Representatives are compelled to address specific local concerns rather than general ideological platforms. The Representative is not merely a party delegate but a direct voice for their unique community.

Furthermore, while gerrymandering remains a challenge in any district system, smaller, more numerous districts are inherently more difficult to manipulate in such a way as to advantage or disadvantage any particular voting bloc on a statewide basis.7Having a large number of small SMDs effectively breaks the tools of gerrymandering—“packing” and “cracking”—when applied at a statewide level. Because districts are so small and numerous, any attempt to “pack” or “crack” voters has only a negligible impact on the overall balance of power, ensuring the statewide seat distribution more accurately reflects the popular vote. While sophisticated mapping techniques could still attempt to draw favorable lines, the sheer number and smaller population sizes of these districts make large-scale, systemic gerrymandering nearly impossible to implement. Moreover, the tendency for small SMDs to naturally encompass local communities of interest can lead to districts that are more organically defined by shared interests, rather than being contorted for partisan ends. This contributes to more competitive elections, which in turn fosters greater voter engagement and responsiveness from elected officials.

Finally, the structure of small SMDs tends to weaken the overbearing influence of national party machines. When candidates can win elections based on their local appeal, their individual merits, and their commitment to community issues—rather than solely on party affiliation or extensive party funding—they are less beholden to party leadership. This empowers Representatives to exercise greater independent judgment, prioritize their constituents’ needs over strict party lines when necessary, and ultimately fosters a more deliberative and less hyper-partisan legislative environment. This focus on constituent-centric representation rather than party-centric is absolutely vital for a truly responsive government. And though it is believed that MMDs would blunt the effects of gerrymandering, the larger district boundaries could nonetheless be much more easily manipulated than the smaller SMDs, and perhaps in ways to disadvantage certain voting blocs.

Conclusion

While the allure of pure proportionality expected from MMDs is understandable, the practical realities and the core purpose of representation for a body like the House of Representatives argue strongly for the adoption of small SMDs. We believe that small SMDs provide the most egalitarian solution, as almost any motivated person can afford to conduct a credible campaign for office in a district of 50,000. In contrast, a substantially larger MMD—which may have 15 to 20 candidates seeking four or five seats—would require significantly more campaign funding, and a major political party affiliation would be essential. Therefore, MMDs are far more party-centric and donor-centric.

Thirty-Thousand.org believes that the ultimate in truly proportional representation would be to implement the solution originally conceived by the first Congress: A minimum of one Representative for every 50,000 residents. Not only would this transform American democracy for the better, but it would also bring the House into compliance with the Constitution’s one-person-one-vote equality requirement!

The ability of small SMDs to dramatically lower campaign costs, forge indelible local connections, enhance direct accountability, and diminish the stifling grip of party influence are not merely minor benefits; they are foundational to a robust and truly representative democracy. By prioritizing accessible, accountable, and localized representation, small SMDs ensure that the House fulfills its paramount duty: To truly represent and serve the diverse citizenry of the nation. The unseen strength of small districts lies in their capacity to empower individual voters and individual Representatives, fostering a healthier, more responsive, and ultimately more democratic government.

Endnote: After this essay was completed, both Grok and Gemini Pro were queried again to estimate the additional diversity that could be expected by having elections in MMDs as opposed to SMDs. As before, they were requested to take into account all the relevant information they could access, but this time also to consider the arguments made in the essay above. Because political campaigns in SMDs are far less costly, they both agreed that SMDs promote a greater socio-economic diversity among the people running for office, offsetting to some extent the greater ideological diversity promised by MMDs. They both also considered the European experience to be very relevant, with Gemini stating that “it’s a critical real-world case study that highlights the potential downsides of proportional voting systems”. And Grok stated that “European PR’s alienation of independent voters reduces MMDs’ effective diversity, further closing the gap with SMDs, which engage local voters through community ties”.

Taking all that into account, Grok revised downward its estimate of additional diversity to be expected from MMDs to zero to 15%. Gemini revised its estimate to 20 to 40% which, to be conservative, is cited in the essay above . Nonetheless, given how that estimate was developed, we realize it is not authoritative. Deeper scholarship and analysis is necessary to produce an estimate that would be generally accepted. However, both AI analyses (linked to above) agreed that SMDs would better ensure that the House truly represents and serves the diverse citizenry of the nation, and we believe that conclusion is manifestly evident based on the arguments made above.

© Thirty-Thousand.org [published 9/12/25, revised 9/29/25]

- 1Congress.Gov: Election Policy Fundamentals

- 2Wikipedia: Proportional representation

- 3This would require over 6,000 Representatives, resulting in an average congressional district population of approximately 50,000.

- 4Grok and Gemini analyses as of September of 2025.

- 5As explained by AI: “This diversity gain, derived from AI analyses of electoral models, is quantified using ideological spectrum models—such as DW-NOMINATE scores that map politicians’ voting records on a left-right axis—and party entropy scores, which measure the informational diversity (or ‘spread’) of party representation in a legislature; higher entropy indicates a broader range of viewpoints, often 20-40% greater in MMDs due to their ability to elect multiple winners per district.”

- 6In a House with over 6,000 Representatives elected from small, 50,000-person districts, dark money’s influence is drastically reduced, as its resources are spread too thin to dominate hyper-local, low-cost campaigns driven by personal engagement—far more so than in larger multi-member districts, where higher costs and party reliance give external funding more traction.

- 7Having a large number of small SMDs effectively breaks the tools of gerrymandering—“packing” and “cracking”—when applied at a statewide level. Because districts are so small and numerous, any attempt to “pack” or “crack” voters has only a negligible impact on the overall balance of power, ensuring the statewide seat distribution more accurately reflects the popular vote.