Small congressional districts virtually eliminate gerrymandering.

Huge congressional districts prevent our

House of Representatives from being a true representation of the American people.

Huge congressional districts prevent our

House of Representatives from being a true representation of the American people.

Communities of interest that are subsumed into massive electoral districts are effectively disenfranchised, thereby preventing diversity and faithful representation in the House.

Eliminate gerrymandering to achieve true representation

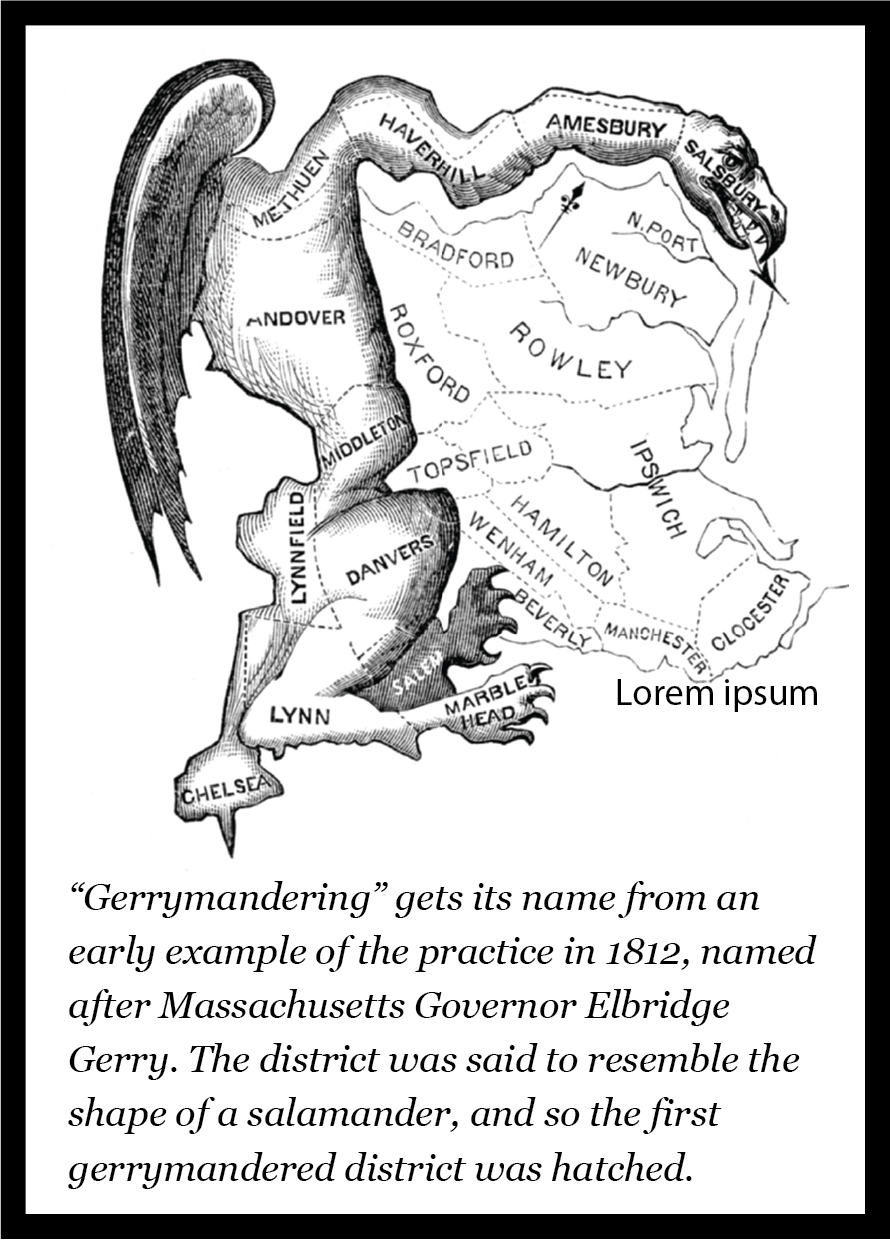

Gerrymandering is the corrupt practice used by politicians and political parties to establish safe seats by manipulating the shape of congressional districts. The twisted and contorted shapes of many these districts, like the ones below, are often intended to predetermine the outcome of elections.

Though the power of political interests to shape congressional districts is an obvious problem, far less obvious is that massive districts are required to enable such extensive gerrymandering. And we do have massive districts: The average U.S. congressional district has approximately 760,000 people and that number grows every year (because the size of the House has long been arbitrarily fixed at 435 Representatives). And the larger the district, the more easily it can be gerrymandered.

Making matters worse, these huge districts are inevitably quite heterogeneous, effectively disenfranchising those voters who are not represented by their district’s majority, or perhaps even by its plurality.

In contrast, districts of 30,000 to 50,000 inhabitants (as was proposed by the first Congress) would be nearly impossible to gerrymander to any significant extent, especially since it wouldn’t be possible to extend district boundaries across great distances to include certain voting blocks while excluding others. In addition, small districts are inherently more compact and would therefore allow many more communities with shared interests and values to have their own voice in the House.

“this Representative Assembly … should be in miniature an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason and act like them.” – John Adams

“Redistricting is a deeply political process, with incumbents actively seeking to minimize the risk to themselves (via bipartisan gerrymanders) or to gain additional seats for their party (via partisan gerrymanders).” – Thomas E. Mann

What is a Gerrymander?

In a republic, voters are supposed to democratically choose their Representatives, but gerrymandered districts effectively allow politicians to choose their voters. Though the gerrymander is a political species known by its varied and grotesque shapes, its monstrous size is what makes it a particularly fierce predator of democracy.

Our Massive Congressional Districts

With an average population of 760,ooo1As a result of the 2020 population census, the national average district size will be equal to the total population of the 50 states (331,108,434) divided by 435., congressional districts are easy to shape so as to achieve whatever political objectives are desired. High priced political consultants with sophisticated software regularly engage in this kind of manipulation. As a result of such gerrymandering, various communities with their own shared interests, values and political perspectives, are effectively disenfranchised by being subsumed into a massive electoral district.

The examples of Illinois’ fourth district and Michigan’s 14th district were provided at the beginning of this article. Another recent example of gerrymandering is provided by North Carolina’s first and 12th districts2These districts, which resulted from the 23rd apportionment as derived from the 2010 population census, were ruled unconstitutional in 2016, and the lines were subsequently redrawn to make the districts more compact. However, the 2016 district map then spurred another round of litigation based on claims of unconstitutional political gerrymandering. This case (Rucho v Common Cause) eventually led to the Supreme Court ruling that partisan gerrymandering claims are not suitable for the courts to decide on because they present a political question that is outside the scope of the federal courts.(below).

Note that both districts had almost exactly the same population size as do most districts within any particular state.3Though the population sizes of congressional districts are nearly identical intrastate, the vary greatly from state to state, which is an egregious violation of the constitutional principle of one person, one vote.

In many cases it is argued that the gerrymandering is well intended. In the case of North Carolina’s 12th district (illustrated above), it was argued that this district allowed African Americans to elect “one of their own” to the House, which may not have been possible otherwise. However, some critics view this type of districting as an apartheid type arrangement which could have the effect of making Americans feel divided. The point is, even if the best of intentions were assumed, lumping one racial group all together, as if they were homogeneous, is obviously a very inadequate solution. Despite a common ancestral origin, the residents in this huge congressional district reside in a variety of distinct local communities, and they undoubtedly embody a diversity of values, backgrounds, and life experiences. Only smaller districts could faithfully represent such diversity.

And with respect to intentional partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts, that problem is here to stay. The Supreme Court has ruled that partisan gerrymandering is a political question that is outside the scope of the federal courts, and therefore such disputes are not justiciable by the courts.4Rucho v. Common Cause.

Advocates for ending the practice of gerrymandering often call for districts to be drawn by bipartisan commissions instead of by one of the political parties. Unfortunately, political games can be played to tip the balance of such a commission for partisan advantage, or sometimes a commission will draw district lines that create safe seats for both major parties. The fairer way to define congressional district boundaries would be to use some type of neutral mathematical algorithm (such as the split line algorithm5Caliper.com: What is a Splitline Algorithm?). But even if such a sensible approach were used, it would not eliminate the problem of inadvertent gerrymandering: The inherent heterogeneity of massive congressional districts makes it impossible, in many instances, to avoid effectively disenfranchising one or more of its communities of interest.

Gerrymandering Illustrated

In order to demonstrate how gerrymandering can be used to effectively disenfranchise various communities of interest, the adjacent illustration portrays a hypothetical state that has a total population of 6.4 million. For the sake of this simplified illustration, imagine that this is a rectangular state where the blue party voters live on the east side, and the red party voters live to the west. And each square represents 50,000 people (in one geographical area). In addition, as a result of a prevailing political duopoly, the voters are only given a choice between a red party or blue party candidate.

Because eight Representatives have been apportioned to this state, it will have to be divided into eight congressional districts containing 800,000 people each, or 16 squares of 50,000 people each. Of course, there are several ways that this state can be divided into eight congressional districts. Three of those ways are illustrated further below as Scenarios A, B and C.

Scenario A illustrates the fairest way to divide this state into eight districts. With three red Representatives and five blue Representatives, the state’s representation is apportioned in the exact same proportion as the underlying population (37.5% red and 62.5% blue) at right.

Scenario B gerrymanders the districts in such a way as to deny the red voters any representation. And the Scenario C gives political control to the red party by gerrymandering the districts in such a way as to completely reverse the underlying proportions, with five red Representatives and only three blue Representatives. The point is that, in districts this large, almost any outcome is achievable in the absence of impartial methods and oversight.

Small Congressional Districts Illustrated

Relative to a representative democracy, small electoral districts have two powerful advantages over large ones. First, they cannot be gerrymandered to any significant extent. In some of the maps of gerrymandered districts provided earlier in this article, the boundaries of these massive districts reached clear across the state to encompass certain populations and exclude others. With small districts it will be impossible to stretch their boundaries to any great extent in order to achieve such a problematic configuration.

The second advantage of small districts is that they will usually be relatively homogeneous (especially in comparison to the current mega-districts). This will make it easier to achieve a truly nonpartisan redistricting. To the extent possible, the focus of creating small districts should be on respecting local communities of interest, as well as existing jurisdictional boundaries, regardless of which political party benefits the most.

Two more scenarios from the hypothetical state will be used to illustrate why smaller districts will create an authentically representative House of Representatives. First, imagine if the congressional district size was reduced from 800,000 to 50,0006The example of 50,000 is used throughout Thirty-Thousand.org because that was the maximum district size proposed as the very first amendment to the Constitution, as explained in Section 1 of this website.. This would result in a total of 128 Representatives being apportioned to this state to represent its 6.4 million inhabitants. This is illustrated as Scenario D.

In a simple two-party (red vs. blue) world, this scenario doesn’t appear to produce much better representation than did Scenario A, as both scenarios ensure that the state’s representation in the House would resemble the underlying population (i.e., 37.5% red and 62.5% blue). However, it does prevent the type of gerrymandering illustrated by Scenarios B and C. And it does overcome the incumbency advantage created by massive electoral districts.

The purpose of these scenarios was to illustrate the various possible districting permutations ranging from equitable to egregiously unfair. However, what this two-tone hypothetical does not represent is the true political mosaic of any state, as our political life is far more vibrant than the red-vs-blue construct that has been imposed upon us. Many who vote for either the red or blue candidate are not enthusiastic members of either the red or blue party. In fact, more U.S. adults identify as politically independent than as either a Republican or a Democrat7Pew Research Center: 6 facts about U.S. political independents., so many may not vote at all because they are turned off by this binary offering.

Even within the two-party realm, many candidates may not be “true blue” or “true red” relative to their party’s mainstream. For example, Bernie Sanders, a socialist, ran as a Democrat in their 2016 presidential primaries even though he had always been elected to the Senate as an independent. And likewise, Donald Trump, a nationalist, ran as a Republican though he had not been long affiliated with that party, and was opposed by many members of that party’s establishment.

Scenario E provides a more realistic illustration of the political life in most states, in which there are many different shades of red, and different shades of blue, and several other political parties and independents as represented by the various colors. There is obviously no way that such a diverse population of 6.4 million people could be divvied up into eight mega electoral districts without many of them feeling alienated, if not disenfranchised, from the electoral process, and therefore less likely to vote.

Like the previous scenario, this one has the state divided into 128 50,000-person congressional districts, each of which will be able to elect a Representative who more faithfully represents their particular community of interest.

Of course, even though such 50,000-person districts will usually be much more politically homogeneous than our current mega districts, they will rarely be completely homogeneous. Referring again to Scenario E, not everyone living in red district #27 (for example) is going to be a red voter. And likewise, not everyone living in green district #60 is going to be a green voter. Nevertheless, they are very likely to be virtually represented by a Representative from another district. That is, a green voter living in a red district will have his or her viewpoint represented in the House by the representative elected from a green district. Likewise, red voters living in a predominately green district still have their views promoted by a Representative elected from a red district, and so on. In this way, the diversity of viewpoints on all issues will have a hearing in our national House.

Not until the House of Representatives becomes much larger will true representation become possible. This is because small congressional districts will lead to a greater diversity of political parties, as many candidates who are known in their local community will be able to afford to run for office without the imprimatur of one of the dominant national parties. Some candidates will run as independents, or Libertarians, or Greens, or any of a number of other political movements.

However, because of our massive congressional districts, the complex mosaic that should be our national political map is forcibly homogenized into a polarized dichotomy of red or blue districts in order to produce a federal legislature largely comprised of nearly indistinguishable politicians, which are voted into office by approximately half of the electorate, many of whom are unenthusiastic about their choices. Unfortunately, the current two-party duopoly will forever oppose enlarging the House to any meaningful extent as the don’t want to lose their nearly absolute hold on political power.

Small and Diverse Districts will Increase Voter Turnout

Voter turnout is quite low in the United States, especially in comparison to other countries around the world.8PewResearch.org: In past elections, U.S. trailed most developed countries in voter turnout. Though there are a variety of reasons for these international variations (including compulsory voting in some countries), voter turnout in the U.S. is much lower than it should be.

For example, though Americans voted in record numbers in the 2020 election, 33.2%9Pew Research Center: Turnout soared in 2020 as nearly two-thirds of eligible U.S. voters cast ballots for president. (or approximately 79 million eligible voters10Based on data provided by ElectionProject.org: “2020 November General Election” spreadsheet.) did not bother to cast a ballot at all. However, that was also a presidential election which increases the turnout. Relative to the House of Representatives, a far more relevant measure is the voter turnout in the midterm elections (when the President is not on the ballot). Voter turnout in the 2018 midterm election was only 50% of eligible voters, which was the highest midterm voter turnout in many decades. In other words, in this midterm election with a historically high turnout, approximately 118 million eligible voters didn’t even bother to cast a vote!11Based on data provided by ElectionProject.org: “2018 November General Election” spreadsheet. Why? According to one poll, two-thirds of non-voters believe that “Voting in elections has little to do with the way that real decisions are made in our country”.12Ipsos.com: “Why don’t people vote?”

These non-voters should not all be dismissed as irredeemably apathetic about, or ignorant of, the importance of voting. Though that is certainly a factor, many eligible voters are understandably cynical about voting, especially if they are turned off by an electoral system that appears to be rigged to favor the Special Interests and career politicians. Both of those problems will be substantially eliminated by small congressional districts. And a significant number of voters who do not identify with either of the dominant political parties would be more likely to participate if they were offered more options. Or they may feel that their vote is of little consequence in such a massive district.

So whatever their reasons are for not voting, it is reasonable to assume that tens of millions of additional voters would participate if they were inspired to do so by at least one of the congressional candidates on their ballot – and who better to do that than candidates living in their local community who actively seek their support?

Low voter turnout is a serious problem as it indicates that much of the citizenry lacks faith in the electoral process. This can create a vicious cycle in which the Representatives therefore appear to only be representing a portion of Americans, which thereby creates greater popular disaffection for the electoral process. In other words, when so many people come to believe that their vote doesn’t count, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is a toxic situation for our republic.

For a variety of reasons, small congressional districts can be expected to encourage many previously disaffected citizens to fulfill their civic duty to vote. As the congressional districts become smaller, that will enable more locally credible candidates to run. And, as a result, previously disaffected citizens will be persuaded (by their local candidates) to participate as voters. Greater voter participation would strengthen our republican form of government as additional citizens come to realize that their vote can actually make a difference. This will not only increase the diversity of our representation in the House, but it will also greatly improve the relationship between the citizenry and their elected Representatives.

Small Districts will Enable True Representation

Political interests will always try to serve themselves first and foremost. One way they have done so in the United States is by drawing House district boundaries that favor the party in power and incumbent politicians, while effectively disenfranchising many voters in the process. The practice is self-evidently corrupt and undemocratic, and undoubtedly helps to discourage voter turnout.

If our Representatives were elected from small districts, the House would be — as the founding fathers intended — a microcosm of the nation as a whole, thereby reflecting the true diversity of the American people. Replacing our massive congressional districts with small & compact ones will allow many communities with shared interests and values to be properly represented in the federal House. In a nation comprised of small and largely homogeneous congressional districts, the House will resemble the nation and its people in miniature. This point was made in 1788 by Melancton Smith during New York’s constitutional convention:

They [the Representatives] should be a true picture of the people, possess a knowledge of their circumstances and their wants, sympathize in all their distresses, and be disposed to seek their true interests. The knowledge necessary for the representative of a free people not only comprehends extensive political and commercial information, such as is acquired by men of refined education, who have leisure to attain to high degrees of improvement, but it should also comprehend that kind of acquaintance with the common concerns and occupations of the people, which men of the middling class of life are, in general, more competent to than those of a superior class.

Using small districts to eliminate gerrymandering is just one of many reasons that representational enlargement will enable we the people to take our government back from the powerful Special Interests and the political ruling class. Explore this website to learn about the other benefits of representational enlargement.

©Thirty-Thousand.org [Article Updated 02/01/22]

Related articles:

NYTimes.com: The New Pennsylvania Congressional Map, District byDistrict

NYTimes.com: How Computers Turned Gerrymandering Into a Science

NYTimes.com: What Is Gerrymandering? And How Does It Work?

FiveThirtyEight.com video: Uh, how does gerrymandering work again? (September 20, 2018)

Ballotpedia.org: Gerrymandering

History.com: How Gerrymandering Began in the US

AmericanProgress.org: How Partisan Gerrymandering Limits Voting Rights

Brookings.edu: A primer on gerrymandering and political polarization

| ◄ Section Four | Section Six ► |

Explore More Topics:

- 1As a result of the 2020 population census, the national average district size will be equal to the total population of the 50 states (331,108,434) divided by 435.

- 2These districts, which resulted from the 23rd apportionment as derived from the 2010 population census, were ruled unconstitutional in 2016, and the lines were subsequently redrawn to make the districts more compact. However, the 2016 district map then spurred another round of litigation based on claims of unconstitutional political gerrymandering. This case (Rucho v Common Cause) eventually led to the Supreme Court ruling that partisan gerrymandering claims are not suitable for the courts to decide on because they present a political question that is outside the scope of the federal courts.

- 3Though the population sizes of congressional districts are nearly identical intrastate, the vary greatly from state to state, which is an egregious violation of the constitutional principle of one person, one vote.

- 4Rucho v. Common Cause.

- 5Caliper.com: What is a Splitline Algorithm?

- 6The example of 50,000 is used throughout Thirty-Thousand.org because that was the maximum district size proposed as the very first amendment to the Constitution, as explained in Section 1 of this website.

- 7Pew Research Center: 6 facts about U.S. political independents.

- 8

- 9

- 10Based on data provided by ElectionProject.org: “2020 November General Election” spreadsheet.

- 11Based on data provided by ElectionProject.org: “2018 November General Election” spreadsheet.

- 12Ipsos.com: “Why don’t people vote?”