“Our Cause is noble. It is the cause of Mankind, and the danger to it is to be apprehended from ourselves.”

George Washington: Hero of the Revolution

Brief Biography

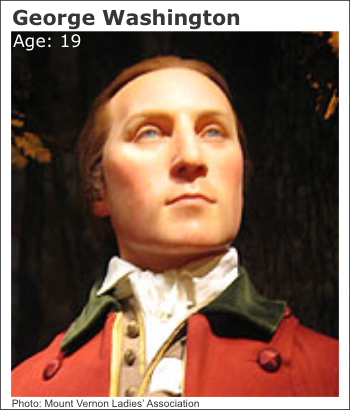

George Washington was born at Bridges Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on February 22, 1732. He was the first child of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball. His father was a middling planter who owned about 10,000 acres of land. Augustine Washington was also very active in public life, serving as sheriff, church warden, and justice of the peace. George Washington received a basic education, studying math, surveying, and reading. In 1749, at the age of 17, he began working as the county surveyor. This job helped him become familiar with the frontier. With that knowledge and experience Washington was appointed major in the Virginia militia in 1752.

One year later Washington was faced with his first major military challenge. In 1753 the French were encroaching on British territory in the Ohio Valley, and the governor of Virginia sent Washington to dislodge them. This event was the beginning of the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Washington was then appointed as aide-de-camp to General Edward Braddock, who was ordered to oust the French in 1755. A year later Braddock died in combat and Washington was promoted to colonel and commander-in-chief of all Virginia troops; in 1758 he was promoted to brigadier.

One year later Washington was faced with his first major military challenge. In 1753 the French were encroaching on British territory in the Ohio Valley, and the governor of Virginia sent Washington to dislodge them. This event was the beginning of the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Washington was then appointed as aide-de-camp to General Edward Braddock, who was ordered to oust the French in 1755. A year later Braddock died in combat and Washington was promoted to colonel and commander-in-chief of all Virginia troops; in 1758 he was promoted to brigadier.

When the French and Indian War ended, Washington resigned his commission and returned to Virginia to concentrate on his family. On January 6, 1759, he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow with two children. He was a dedicated stepfather and a skilled farmer. He also became actively involved in politics and was elected as representative from Frederick County to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758. He then served as justice of Fairfax county from 1760 to 1774.

In the late 1760s and early 1770s tension had begun to mount between Britain and the colonies, particularly over taxation and importation issues. As a legislator, Washington was very involved in colonial affairs. In 1774 he helped write and pass the Fairfax Resolves, which formed the Continental Association and the Continental Army. When the disputes with Britain turned into war, the Continental Congress on June 15, 1775, unanimously elected Washington to command the Continental Army.

In the late 1760s and early 1770s tension had begun to mount between Britain and the colonies, particularly over taxation and importation issues. As a legislator, Washington was very involved in colonial affairs. In 1774 he helped write and pass the Fairfax Resolves, which formed the Continental Association and the Continental Army. When the disputes with Britain turned into war, the Continental Congress on June 15, 1775, unanimously elected Washington to command the Continental Army.

Throughout the American Revolution, from 1775 to 1783, Washington served as de facto chief executive of the United States. He proved to be a gifted leader with good administrative skills and political acumen. When the war was finally won, Washington handed over his powers to Congress at Annapolis, Maryland, and returned home to Mount Vernon to retire.

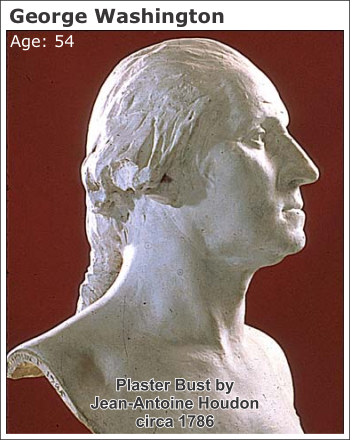

However, Washington was soon called back to serve his country. The Articles of Confederation proved too weak to hold the new country together, and in 1786 Washington described the situation as “anarchy and confusion.” In an effort to revise the articles, Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787. In 1789 he was unanimously elected as the first President of the United States. He began his term by stating: “I walk on untrodden ground. There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.”

Washington immediately became involved in the creation of the new government. He created the first Cabinet, establishing the departments of State, Treasury, and War. Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) became the first Secretary of the Treasury, and together with Washington he developed the country’s economic system. On July 4, 1789, Washington signed the first bill passed by Congress. It gave the government the right to tax and was used to pay the debt accumulated by the Revolution and establish American credit at home and abroad. Washington also approved the Federalist financial program and other proposals by Hamilton, including funding the national debt, assuming state debts, establishing a federal bank, creating a coinage system, and establishing an excise tax. In addition to these economic policies, Washington presided over the expansion of the country from 11 to 16 states.

Washington immediately became involved in the creation of the new government. He created the first Cabinet, establishing the departments of State, Treasury, and War. Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) became the first Secretary of the Treasury, and together with Washington he developed the country’s economic system. On July 4, 1789, Washington signed the first bill passed by Congress. It gave the government the right to tax and was used to pay the debt accumulated by the Revolution and establish American credit at home and abroad. Washington also approved the Federalist financial program and other proposals by Hamilton, including funding the national debt, assuming state debts, establishing a federal bank, creating a coinage system, and establishing an excise tax. In addition to these economic policies, Washington presided over the expansion of the country from 11 to 16 states.

After his first term as president ended in 1792, Washington had plans to retire from political life. His colleagues, however, persuaded him to serve one more term. On February 13, 1793, Washington was once again unanimously elected to the presidency. His second term focused on the young country’s foreign policy. In 1793 Washington announced the Neutrality Proclamation to keep the United States out of all foreign disputes. Relations with France and Britain were tested during Washington’s tenure, but he managed to keep peace. By 1796 Washington had grown tired of the demands of political life and once again decided to retire. This time he was able to have his way and pacify critics who called him a closet monarchist. On September 17, 1796, Washington published his Farewell Address and returned home to Mount Vernon following the next presidential election.

His retirement was brief, as Washington was called again to public service in 1798. The United States was on the verge of war with France and President John Adams (1797-1801) asked Washington to raise an army for defense. Washington answered the call to duty, but the threat quickly subsided due to diplomatic negotiations. Once again he resigned his commission and returned to Mount Vernon. Soon after returning home, Washington, suffering from a serious throat infection, died on December 14, 1799. After George Washington’s death, Congress unanimously agreed to erect a marble monument, called the Washington Monument, in the nation’s capital to pay tribute to the country’s first president.

Source of Biography: Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Gale Group, 1999.

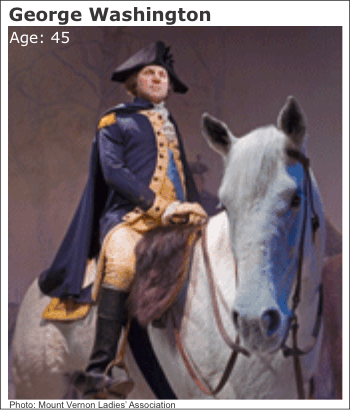

George Washington before the Battle of Long Island

“The time is now near at hand, which must probably determine whether Americans are to be free men or slaves; whether they are to have any property they can call their own; whether their houses and farms are to be pillaged and destroyed, and themselves consigned to a state of wretchedness from which no human efforts will deliver them.

“The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of a brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer, or to die.

“Our own, our country’s honour call upon us for a vigorous and manly exertion; and if we now shamefully fail, we shall become infamous to the whole world.

“Let us, then rely on the goodness of our cause, and the aid of the Supreme Being, in whose hands victory is, to animate and encourage us to great and noble actions.

“The eyes of all our countrymen are now upon us, and we shall have their blessings and praises, if happily we are the instruments of saving them from the tyranny mediated against them.

“Let us, therefore, animate and encourage each other, and shew the whole world that a free man, contending for liberty on his own ground, is superior to any slavish mercenary on earth.

“Liberty, property, life, and honor are all at stake; upon your courage and conduct rest the hopes of our bleeding and insulted country. Our wives, children, and parents expect safety from us alone, and they have every reason to believe that Heaven will crown with success so just a cause.

“The enemy will endeavor to intimidate by show and appearance; but, remember, they have been repulsed on various occasions by a few brave Americans. Every good soldier will be silent and attentive – wait for orders and reserve his fire until he is sure of doing execution.”

Several sources indicate that this was a speech given by Washington before the battle of Long Island, August 26, 1776. Another source attributes it to General Orders of July 2, 1776.

Explore More Topics: