Article the first: The Founders’ proposal for a much larger House

The very first amendment proposed in our Bill of Rights has never been ratified.

The very first amendment proposed in our Bill of Rights has never been ratified.

The intended purpose of “Article the first” was to ensure that the number of Representatives would forever increase along with the total population. An arithmetically complex amendment, this proposal was affirmed by many states before a subtle, but fatal, defect in its formulation eventually became evident.

Article the first of the Bill of Rights

After the Constitution was proposed, many citizens believed that the success of the new republic would be predicated upon the number of Representatives in the U.S. House forever increasing in proportion to the nation’s total population. In fact, that is what was promised by the founders. For example, a prominent framer of the Constitution predicted, in 1787, that “the House of Representatives will, within a single century, consist of more than six hundred members”.1James Wilson, one of the signatories of the Constitution, speaking at the Pennsylvania ratification convention. See: Farrand’s Records, Volume 3, pages 159-160. November 30, 1787 Yet over two centuries later, Congress has granted only 435 Representatives to we the people, which brings us to the problem at hand.

Though the Constitution established the maximum number of Representatives at one for every 30,000 people, it failed to explicitly require a corresponding minimum. According to Federalist 55, this failure drew the most criticism of any provision in the proposed constitution. James Madison (known as the “Father of the Constitution”) later confessed that he had “always thought this part of the constitution defective” when he introduced his proposal to rectify it as one of his several proposed amendments to the Constitution.

It is therefore not surprising that the very first constitutional amendment passed by Congress was intended to fix this defect by requiring a minimum number of Representatives proportionate to the total population. Strangely, this proposal was never sent to the states for ratification. Instead, a seemingly identical but defective version was substituted for it, which effectively sabotaged the implementation of this solution.

“[It is] a power inconsistent with every principle of a free government, to leave it to the discretion of the rulers to determine the number of representatives of the people. There was no kind of security except in the integrity of the men who were intrusted; and if you have no other security, it is idle to contend about constitutions.”

– Melancton Smith

“It is the sense of the people of America, that the number of Representatives ought to be increased, but particularly that it should not be left in the discretion of the Government to diminish them, below that proportion which certainly is in the power of the Legislature as the constitution now stands… I confess I always thought this part of the constitution defective…” – James Madison

Twelve Constitutional Amendments Were Proposed

In June of 1789, a year after our Constitution was ratified by the states, James Madison proposed a list of constitutional amendments to the first congress. Derived largely from the numerous amendments that had been proposed by the states’ ratification conventions, the purpose of Madison’s proposals was to address the most persistent objections that had been raised against the proposed constitution (largely by the antifederalists).

During the subsequent 15 weeks, Congress debated Madison’s proposals, modifying or rejecting them, and proposing a variety of additional amendments in the process. As various proposals were passed by either chamber, they were quoted verbatim in the local newspapers. It is easy to imagine that as they were reported in the press, they would have generated a tremendous amount of discussion among Americans who took an interest in such matters. In particular, these proposals would have been read with great anticipation by many of the state legislators who were expecting to deliberate upon them after they were formally proposed by Congress.

In the waning days of their very first session, Congress passed the resolution proposing twelve articles of amendment to the Constitution, which was formally submitted to the states’ legislatures in October of 1789. Within 15 months, the state legislatures ratified the last ten of these twelve proposals – the third through twelfth – as the first ten amendments to our Constitution. Hence, Article the third became our First Amendment (concerning freedom of religion, speech & press) … and Article the fourth became our Second Amendment (concerning the right to keep and bear arms) … and so forth.

So what about the first two Articles? Two centuries later, Article the second was finally ratified as our twenty-seventh amendment.2National Archives: A Record-Setting Amendment And Article the first, which is the subject of this article, has never been ratified. Therein lies a fascinating story which we will return to later in this article.

It is helpful to understand that the nature of the first two Articles of amendment is quite different than that of the last ten which were initially affirmed by the states. The first and second Articles of amendment do not extend rights. Instead, they impose constraints which apply only to the Representatives in the House. In contrast, Article the third (first amendment) through Article the tenth (eighth amendment) guarantee specific rights to all citizens. And the last two articles affirm that the unenumerated rights are retained by the people, and that the undelegated powers are retained by the states.

These last ten articles – which became the first ten amendments to our Constitution – had been previously thought unnecessary simply because the Constitution explicitly limits the scope of federal authority to the powers enumerated therein. That is, the Constitution did not grant the federal government any authority to regulate speech, religion, the right to bear arms, or any of the other areas addressed by these ten amendments. That notwithstanding, many of the delegates to the states’ conventions were wisely apprehensive about the natural tendency of national governments to become tyrannical. They believed that nothing should be taken for granted with respect to protecting our liberties relative to the new national government (which had been established only 15 months before the Bill of Rights was proposed by Congress).

The antifederalists’ insistence on these constitutional amendments has been well vindicated by subsequent history. It is difficult to imagine how degraded our quality of life would be today had these explicit guarantees not been ratified to our Constitution. However, in the case of Article the first we need not rely on our imaginations. The adverse consequences resulting from the failure to ratify Article the first, in its intended form, are explained in the other sections of this website.

Before we turn to the fascinating story of Article the first, we must first understand the defect which it was intended to correct.

The Defective Part of the Constitution

The Constitution requires that the “Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand”, and that these Representatives “shall be apportioned among the several States … according to their respective Numbers” (see box). In other words:

- The average constituency size (or district size) must be at least 30,000 people.

- The Representatives shall be apportioned to the states in proportion to their relative population sizes.3For example, a state with 10% of the total population should receive approximately 10% of the total Representation in the U.S. House. The significance of this formulation was even more consequential at the time because it also determined the allocation of the federal tax burden to the states (until the 16th amendment was ratified in 1913).

However, though the Constitution established a minimum average constituency size of 30,000 for the Representatives, it failed to establish a corresponding maximum size (which would be required to determine the minimum size of the House). During the states’ conventions, this omission generated more criticism and greater deliberation than any other issue4For example, approximately 30% of the 85,000-word transcript from the New York ratification convention was devoted exclusively to this concern as Madison acknowledged in Federalist 55.5 Federalist 55: “Scarce any article, indeed, in the whole Constitution seems to be rendered more worthy of attention, by the weight of character and the apparent force of argument with which it has been assailed.”

Consequently, when Madison proposed his list of amendments to the first congress, his second proposal was intended to remedy the Constitution’s failure to establish a minimum House size. In support of his proposal, Madison argued that “the number of Representatives … should not be left in the discretion of the Government”. Referring to this omission in the Constitution, Madison confessed that he had “always thought this part of the constitution defective”.6Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 1st Congress, 1st Session, 8-June-1789, page 457

The Intended First Article and its Defective Twin

Approximately ten weeks after Madison proposed his amendments, and after considerable debate thereon, the House passed a proposal (on August 21, 1789) to correct the defect in the Constitution. Their solution was to create a three-tier mathematical formulation which would establish a maximum average constituency size (or district size) of 50,000 once the nation’s total population exceeded ten million. Consequently, the minimum size of the House would be one Representative for every 50,000 people, thereby complementing the maximum House size of 1:30,000 already established by the Constitution.

This was the first of 17 proposed amendments that the House subsequently sent over to the Senate for their consideration. Addressing them in sequence, the Senate’s first modification was to propose their own version of the first Article. Like the House’s version, the Senate’s version required that the number of Representatives forever increase in direct proportion to the total population, but at the slightly slower rate of one for every 60,000. Therefore, at this point in time, at least two thirds of both chambers agreed that the minimum size of the House should forever be directly proportional to the nation’s total population, disagreeing only with respect to the ratio.7Whereas the House’s first Article established the minimum House at 1:50,000 for all population levels above ten million, the Senate’s version would increase the size of the House at the rate of 1:60,000 for all population levels above seven million.

The Senate proceeded to propose numerous modifications to the House’s remaining proposed amendments, the net effect of which was to reduce the total number of amendments from 17 to 12, mostly through consolidation and concision. The Senate sent their proposed modifications to the House for their consideration.

On September 21st, the House accepted nearly half of the Senate’s modifications and rejected the rest. One of those rejected was the Senate’s version the first Article. The Senate immediately retracted that particular proposal, but insisted on all of the others that the House had rejected. As a result, the House’s first Article – which established the minimum size of the House at one Representative for every 50,000 – became the very first constitutional amendment ever to be approved by two-thirds of both chambers.8An elaboration of this history will be provided in a separate article.

The House and Senate then agreed to create a joint Conference Committee to resolve the remaining areas of disagreement relative to the Senate’s proposed modifications. Both chambers explicitly instructed the Conference Committee to focus only on the areas of disagreement relative to these amendments. Therefore, the first Article was indisputably outside of the committee’s scope.

The Conference Committee had less than three days to resolve the remaining disagreements between the House and Senate with respect to the constitutional amendments (while also dealing with many other substantial legislative matters). These were the waning days of the very first session of the first Congress and, after nearly seven months of intense legislative work on innumerable matters, the delegates were eager to return to their homes.

On September 24th the Conference Committee’s report, which was delivered to both chambers of Congress, proposed several recommendations intended to settle the remaining areas of disagreement. Strangely, this report contained a rather cryptic and oddly arranged instruction pertaining to the first Article despite the fact it was outside of their area of consideration. As explained in The History of Article the first9To be published in September of 2022. there is no way that this instruction could have been heard or understood by either chamber, especially since its fully revised wording was never presented for deliberation.

As a result of this cryptic instruction, an alternate version of Article the first was created and then proposed to the states along with the additional eleven amendments. And though this alternate version appears to be identical to the version already passed by Congress, it would not only produce an absurdly different result, but it also contained an inexplicable mathematical defect that effectively rendered it unusable. As explained later, this defective version could not have possibly been intended by Congress, and they would have never wittingly approved it.

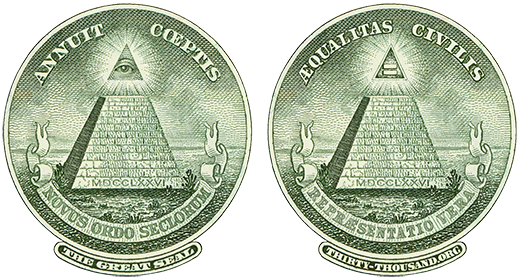

Below, the intended version is shown on the left and the defective version is shown on the right.

If you did not detect, or comprehend, the profoundly consequential difference between these two versions, then you are in very good company: Some of the most distinguished and well-educated gentlemen of the late 1780s, along with numerous historians and scholars since then, also failed to comprehend the difference. This difference will be identified and explained later in this section. For now, the essential point to understand is that when the Bill of Rights was finally sent to the states’ legislatures (on Oct 2, 1789), its first Article appeared to be identical to the version passed by the House (on the left above) that had previously been published in various newspapers.

It is probably apparent to most readers that neither version of Article the first can be easily comprehended. There are two reasons for this. First, the proposal seems arithmetically convoluted (even for those who are fond of math). Second, owing to the framers’ penchant for conciseness, Article the first is densely worded. These two factors combine to make this 99-word amendment nearly incomprehensible for casual readers. The near impenetrability of its wording will ultimately enshroud the fatal alteration made by members of the joint committee. Moreover, the provision’s near imperviousness also explains why surprisingly little scholarly attention has been devoted to this very consequential historical artifact (and why so few people are even aware of it).

The Intended first Article

As stated above, the intended version of Article the first was passed by two-thirds of the House on August 21st, and then agreed to by two-thirds of the Senate a month later. This proposed amendment was to establish a minimum House size to complement the maximum House size already established by the Constitution (of one Representative for every 30,000 people).

The intended first Article’s formulation consists of three tiers as follows:

- Tier 1: A minimum of one Representative for every 30,000 for all population levels below three million. (This tier was never relevant because, as expected, the first census counted more than three million people.)

- Tier 2: The greater of 100 or one Representative for every 40,000 people for all population levels up to eight million.

- Tier 3: The greater of 200 or one Representative for every 50,000 people for all population levels greater than eight million.

The lower boundary in the chart below illustrates the minimum size established by the intended version of Article the first (for all population levels up to 35 million). The essential point to understand is that once the nation’s population exceeds ten million, the minimum number of Representatives would forever be one for every fifty thousand.

Note that the minimum size specified by this proposal complements the upper boundary already established by the Constitution (of one Representative for every 30,000). Therefore, the first Article was intended to require that, after each decennial census, future congresses select any House size between those upper and lower limits.

The First Article’s Defective Twin

As mentioned above, though the intended version had been approved by two-thirds of both chambers, it was not the one sent to the states ten days later. And though the substitute version appears identical to the intended version, it contains a subtle alteration which effectively sabotaged the proposal’s purpose. That alteration is revealed in the comparison below.

Note that the fourth instance of the word “less” in the intended version (on the left) was incongruously replaced by the word “more” (on the right), thereby making the formulation both defective and absurd, as explained below. It was this defective version that was inexplicably sent to the states.

More is Less

By simply substituting “more” for “less” in the third tier, the defective proposal becomes spectacularly different than what was intended in four different respects.

First, for all population levels over eight million, this alternate version subverted the purpose of Article the first by converting the intended minimum House size into its maximum – indicated by ① in the chart below. This would have inexplicably contradicted the maximum already established by the Constitution and frequently touted in the Federalist Papers! In fact, during the deliberations leading up to the proposal of the first Article, there was never any broad support for overriding the constitutional maximum of 1:30,000 (except for the Senate’s version of the first Article10Recall that the Senate’s version proposed a fixed ratio of 1:60,000 which would have simultaneously overridden the Constitution’s maximum size while establishing an equivalent minimum size.). Therefore, it is absolutely inconceivable that two-thirds of both chambers would have voted to reduce the maximum number of Representatives allowed by the Constitution.

Secondly, and consequently, this alteration caused the transitional minimum of 200 (between the second and third tiers) to continue as a permanent fixed minimum – indicated by ② in the chart below.

These first two adverse consequences are illustrated in the chart below (which may be easier to understand if compared with the previous chart).

The notion of merely establishing a minimum House size of 200 Representatives would have been quite the opposite of the proportional formulation agreed to by two-thirds of both chambers a few days earlier (of one for every 50,000), and quite the opposite of the alternate formulation proposed by the Senate (of one for every 60,000). There is nothing in the historical record to suggest that two-thirds of both chambers would suddenly reverse their thinking and, even had they done so, it would have certainly engendered some furious deliberations – and yet there were none.

The third adverse consequence results from flipping the third tier’s minimum formulation into a maximum one, creating in an absurd outcome upon the transition from Tier 2 to Tier 3. Recall that the upper limit of Tier 2 is reached when there is a minimum of 200 Representatives, which would happen at a total population of eight million (200 × 40,000). The corresponding maximum size of the House, per the Constitution, would be 266.118,000,000 ÷ 30,000 = 266.7 → round down to 260.

Adding a single person to the population, raising it to 8,000,001, would cause the calculation to be governed by Tier 3 (instead of Tier 2). At that point, pursuant to the Tier 3 formulation, the maximum size would be 160128,000,001 ÷ 50,000 = 160.00002 → round down to 160. (overruling the Constitution’s maximum). Therefore, whereas the minimum House size is 200 for a population of eight million, increasing the population by a single person results in a maximum House size of 160 indicated by ③ in the chart above. In this scenario, Congress would be forced to eliminate 40 Representatives as a result of a population increase! Not only is this patently absurd, but it leads us to defective version’s fatal flaw.

The resulting fatal flaw is the fourth adverse consequence of the defective wording, and it is the most indefensible of them all: An unsolvable mathematical problem which rendered it nonsensical – indicated by ④ in the chart above. At the point where the maximum size of the House is dropped to 160, the corresponding minimum size is 200. In fact, for any population size between eight and ten million, the maximum size of the House would be below the minimum! Had this defective version been ratified, it would have led to a constitutional crisis after the 1820 census tallied the total population at approximately nine million.13The 1820 census tallied an apportionment population total of 8,969,878. Per the defective version of the first Article, the maximum size of the House would be that total divided by 50,000, or 179 Representatives. (This would have been less than the previous apportionment.) However, this version of the first Article also required that, for all population totals between eight and ten million, the minimum size of the House is 200, thereby creating a mathematical impossibility. As it turns out, in the absence of the proposed (and defective) first Article, Congress authorized a total of 213 Representatives, which was in compliance with the intended version of Article the first.

Even if it had been Congress’s intent to simply establish a fixed minimum size of 200 beyond Tier 2, they could have simply deleted the last ten words of the proposed amendment.14That is, deleted “nor less than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons’’. That deletion would have not only avoided unnecessarily contradicting the maximum size established by the Constitution, it would have also prevented the indefensible consequences described above.

For a more detailed explanation of the formulations in both versions of the first Article, read Article the first’s Mysterious Defect.

It is most likely that those who hastily conceived of this surreptitious alteration did not realize, until it was too late, that it also created this mathematical defect. Had this modification been heard by the members of either chamber, a number of these well-educated gentlemen would have quickly detected this embarrassing absurdity before it could be proposed to the states.

Initially, many states ratified this defective proposal, evidently assuming that it was the same as the sensibly written version they had previously read in the newspapers. In time, the defect became noticed, with one state legislator observing that the proposal contained “an absurdity and a contradiction”. Though it was initially ratified by most of the states, it was later abandoned. There are two obvious reasons for its abandonment: Either its defect became apparent, or because it would have been otherwise inconsequential in its effect in the long term. It cannot be doubted that, had Article the first been sent to the states in its intended (non-defective) form, it would have been ratified to the Constitution.

Proposed & Forgotten

Though the first Congress approved a sensibly worded amendment to correct the defect in the Constitution, as many states had demanded, a few days later a defective version of that amendment was sent to the states as the first of twelve amendments in the Bill of Rights.

As explained in The History of Article the first, the defective version was likely created by some crafty parliamentary legerdemain without most of the Congressmen even being aware of it. In fact, of all the proposals that were sent to the states for ratification, the first Article is the only one that was never stated in its full form in either chamber!

Though most of the states ratified the defective version, its deficiencies were eventually discovered thereby causing it to be subsequently abandoned. The would-be first amendment then disappeared into America’s memory hole, waiting two centuries for its crippling defect to be rediscovered. Given the widespread demand for this amendment at that time, it certainly would have been ratified had it been proposed to the states in its intended (or non-defective) form, which we call the Founders’ Rule. And had the Founders’ Rule been ratified, the benefits to our republic would have been innumerable, as explained in the other sections of this website.

© Thirty-Thousand.org [Article Updated 03/21/22]

| ◄ Section One | Section Three ► |

Explore More Topics:

- 1James Wilson, one of the signatories of the Constitution, speaking at the Pennsylvania ratification convention. See: Farrand’s Records, Volume 3, pages 159-160. November 30, 1787

- 2National Archives: A Record-Setting Amendment

- 3For example, a state with 10% of the total population should receive approximately 10% of the total Representation in the U.S. House. The significance of this formulation was even more consequential at the time because it also determined the allocation of the federal tax burden to the states (until the 16th amendment was ratified in 1913).

- 4For example, approximately 30% of the 85,000-word transcript from the New York ratification convention was devoted exclusively to this concern

- 5Federalist 55: “Scarce any article, indeed, in the whole Constitution seems to be rendered more worthy of attention, by the weight of character and the apparent force of argument with which it has been assailed.”

- 6Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 1st Congress, 1st Session, 8-June-1789, page 457

- 7Whereas the House’s first Article established the minimum House at 1:50,000 for all population levels above ten million, the Senate’s version would increase the size of the House at the rate of 1:60,000 for all population levels above seven million.

- 8An elaboration of this history will be provided in a separate article.

- 9To be published in September of 2022.

- 10Recall that the Senate’s version proposed a fixed ratio of 1:60,000 which would have simultaneously overridden the Constitution’s maximum size while establishing an equivalent minimum size.

- 118,000,000 ÷ 30,000 = 266.7 → round down to 260.

- 128,000,001 ÷ 50,000 = 160.00002 → round down to 160.

- 13The 1820 census tallied an apportionment population total of 8,969,878. Per the defective version of the first Article, the maximum size of the House would be that total divided by 50,000, or 179 Representatives. (This would have been less than the previous apportionment.) However, this version of the first Article also required that, for all population totals between eight and ten million, the minimum size of the House is 200, thereby creating a mathematical impossibility. As it turns out, in the absence of the proposed (and defective) first Article, Congress authorized a total of 213 Representatives, which was in compliance with the intended version of Article the first.

- 14That is, deleted “nor less than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons’’.